Lab #2

Visible Language

Technologies of Text, Spring 2018

Museum of Fine Arts, Boston

January 19, 2018

Lab Introduction

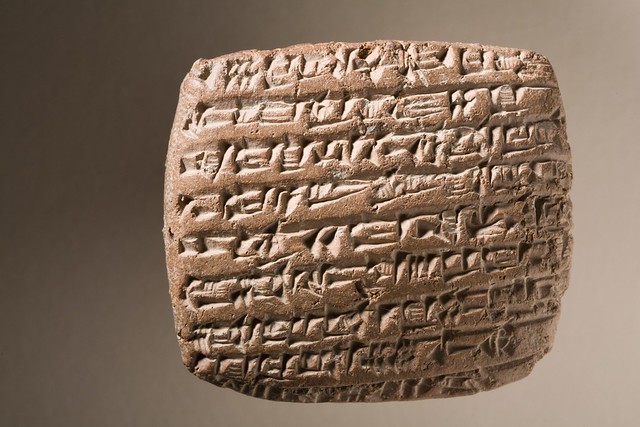

We begin our visit to the MFA by talking about the cuneiform tablet: the earliest known form of writing and one that help us think about what media mean in their infancy and how those meanings evolve. Cuneiform began as a medium for business, accounting, and even computing—recall “this is the procedure” from Gleick—and slowly became a medium for art and literature. Media are created for certain purposes, in other words, but are adopted and adapted for others.

A cuneiform tablet photographed by Ashley Van Haeften

In the MFA’s Art of the Ancient World Collections, you can find examples of ancient writing from many cultures across thousands of years: Babylonian, Egyptian, Etruscan, Greek, Nubian, and Roman. Because this is an art museum and not a library, this writing can primarily be found on objects rather than in books (don’t worry, we will see some ancient books later this semester). But of course, writing then as now was a diverse practice, and books were only one of many textual media.

Today’s lab will be an exercise in discovery, observation, and comparison. We want to get beyond tourism, in which we would look at the objects with some awe and then move on, and toward analysis. Few of you will be able to read the ancient media we are looking at—though you can of course read the summaries and translations provided in the various exhibits—so we will attend primarily to relationships between material and meaning.

Lab Activity

This will be an exercise in attentive looking. Choose two distinct textual artifacts from two different ancient cultures and carefully compare them. Spend time with your chosen artifacts. We can’t hold them, as we will some rare books later this semester, but look as closely as you possibly can at them. Take notes as you observe that you can use later to write your fieldbook entry. Use your two chosen objects to think comparatively. How are the two objects you’ve chosen similar? How are they distinct? How do these objects make their meaning? Consider these questions:

- What is the medium, and what are its materials? How was each artifact created?

- How do the material facts of your artifacts’ creation affect their textuality? Can you discern a relationship between the materials and the way people wrote with or on those materials?

- What can you say about the mode of writing on each artifact? How is language represented? How do you imagine these different modes of representation would shape reading and writing processes? What is the relationship between text and other kinds of representation (images, etc.) on your chosen artifacts?

- If there is a translation or summary of a text available, how does that message relate to its medium?

- How do you think this textual object was used, or intended to be used? How does its form signal those uses?

- How do your artifacts signal the relationship of texts to issues of class, education, wealth, and so forth?

- Recall also our recent readings. How might you consider these artifacts in light of what we learned from Plato’s “Phaedrus,” McLuhan, Liu, the first chapters of The Information, and/or Butler’s “Speech Sounds?” Are there insights from these texts that help you see these artifacts in a new light?

In your analysis, you should not simply list similarities and differences: e.g. the cuneiform tablet was small, but the hieroglyphic tomb wall was big. A comparative analysis should interpret those similarities and differences, thinking through what they might tell us about the audience(s), purpose(s), and meaning(s) of writing in these different media, cultures, and time periods.

LABS