The Unessay

Assignment Overview:

- Form can vary widely!!

- Students generally work individually, though I am open to collaborative proposals.

- Unessay 1 due March 5 by 5pm

- Unessay 2 due TBA

- 30% of total grade

The Nitty-Gritty

Twice this semester you will develop unessay projects.

- I highly prize creative takes on this assignment. Before jumping into typical paper writing mode, consider other media, presentation styles, and modes of critical engagement you might employ instead.

- This is a hands-on course about media and technology: I would be thrilled to see unessays that do rather than (only) describe. Consider using your unessay assignments to get your hands dirty (perhaps literally) with some of the media we discuss in class.

- Take advantage of my advice and help as you develop your unessay ideas. That’s what I’m here for!

You may complete your unessays on your own schedule, but they must be turned in by the listed due dates. I would strongly advise you not to put the assignment off. To motivate you to work earlier, I am happy to offer feedback on drafts submitted at least one week in advance of a given deadline. We will also workshop ideas during class sessions well in advance of each deadline.

I will also show you some stellar examples of unessays in the weeks leading up to the first deadline, and would be happy to show you others during office hours. I have a growing collection of stunning student unessay work that I love revisiting.

Assignment Background

Thanks to Daniel Paul O’Donnell for this brilliant assignment, which I’ve only slightly modified for our class. For more on the research behind the Unessay assignment, see the work of Emma Dering and Matthew Galea.

The essay is a wonderful and flexible tool for engaging with a topic intellectually. It is a very free format that can be turned to discuss any topic—works of literature, of course, but also autobiography, science, entertainment, history, and government, politics, and so on. There is often something provisional about the essay (its name comes from French essai, meaning a trial), and almost always something personal.

Unfortunately, however, as Wikipedia notes,

In some countries (e.g., the United States and Canada), essays have become a major part of formal education. Secondary students are taught structured essay formats to improve their writing skills, and admission essays are often used by universities in selecting applicants and, in the humanities and social sciences, as a way of assessing the performance of students during final exams.

One result of this is that the essay form, which should be extremely free and flexible, is instead often presented as a static and rule-bound monster that students must master in order not to lose marks (for a vigorous defense of the flexible essay, see software developer Paul Graham’s blog). Far from an opportunity to explore intellectual passions and interests in a personal style, the essay is transformed into a formulaic method for discussing set topics in five paragraphs: the compulsory figures of academia.

Enter the Unessay

By contrast, the unessay is an assignment that attempts to undo the damage done by this approach to teaching writing. It works by throwing out all the rules you have learned about essay writing in the course of your primary, secondary, and post secondary education and asks you to focus instead solely on your intellectual interests and passions. In an unessay you choose your own topic, present it any way you please, and are evaluated on how compelling and effective you are. Here are the guidelines:

- You choose your own topic. The unessay allows you to write about anything you want provided you are able to associate your topic with the subject matter of the course and unit we are working on. You can take any approach; you can use as few or as many resources as you wish; you can even cite the Wikipedia. The only requirements are that your treatment of the topic be compelling: that is to say presented in a way that leaves the reader thinking that you are being accurate, interesting, and as complete and/or convincing as your subject allows.

- You can present it any way you please. There are also no formal requirements. Your unessay can be written in five paragraphs or twenty-six. If you decide you need to cite something, you can do that anyway you want. If you want to use lists, use lists. If you want to write in the first person, write in the first person. If you prefer to present the whole thing as a video, present it as a video. Use slang. Or don’t. Write in sentence fragments if you think that would be effective. In other words, in an unessay you have complete freedom of form: you can use whatever style of writing, presentation, citation, or media you want. What is important is that the format and presentation you do use helps rather than hinders your argument about the topic. Perhaps most importantly, the unessay allows you to use media deliberately and thoughtfully. You can create a digital unessay, or you can create an analog project—in fact, many of the most compelling unessays I’ve seen have been entirely analog.

- You are evaluated on how compelling and effective you are. If unessays can be about anything and there are no restrictions on format and presentation, how are they graded? The main criteria is how well it all fits together. That is to say, how compelling and effective your work is.

An unessay is compelling when it shows some combination of the following:

- it is as interesting as its topic and approach allows

- it is as complete as its topic and approach allows (it doesn’t leave the audience thinking that important points are being skipped over or ignored)

- it is truthful (any questions, evidence, conclusions, or arguments you raise are honestly and accurately presented)

- it makes an argument, taking a particular point of view on the topic. A good unessay doesn’t just describe, it synthesizes and analyzes.

In terms of presentation, an unessay is effective when it shows some combination of these attributes:

- it is readable/watchable/listenable: i.e. the production values are appropriately high and the audience is not distracted by avoidable lapses in presentation.

- it is well crafted: the assingment’s invitation to write in different modes (using slang, etc.) does not mean the unessay needn’t be copyedited. Deliberate stylistic choices can help convey your message, while needless errors will distract from your message.

- it is appropriate: i.e. it uses a format and medium that suits its topic and approach.

- it is attractive: i.e. it is presented in a way that leads the audience to trust the author and his or her arguments, examples, and conclusions.

Why Unessays Are Not a Waste of Your Time

The unessay may be quite different from what you are used to doing in English class. If so, a reasonable question might be whether I am wasting your time by assigning them. If you can write whatever you want and present it any way you wish, is this not going to be a lot easier to do than an actual essay? And is it not leaving you unprepared for subsequent instructors who want you to right the real kind of essays?

The answer to both these questions is no. Unessays are not going to be easier than “real” essays. There have fewer rules to remember and worry about violating (actually there are none). But unessays are more challenging in that you need to make your own decisions about what you are going to discuss and how you are going to discuss it.

And you are not going to be left unprepared for instructors who assign “real” essays. Questions like how to format your page or prepare a works-cited list are actually quite trivial and easily learned. You can look them up when you need to know them and, increasingly, can get your software to handle these things for you anyway. In our class, moreover, I will be giving you separate instruction on what English professors normally expect to see in the essays you submit to them.

But even more importantly, the things you will be doing in an unessay will help improve your “real” ones: excellent “real” essays also match form to topic and are about things you are interested in; if you learn how to write compelling and effective unessays, you’ll find it a lot easier to do well in your “real” essays as well.

Model Unessays

Below are some fantastic digital unessays that students have submitted. These examples don’t necessarily model the content of your assignments, as some were completed for classes covering very different topics, but hopefully they will give you a sense of what kinds of work you might complete.

- Operation Critique

- Beyond the Words: Text in Art

- Programming a Medium

- Know Code (music available on request)

- ESSAIS1580

- The Evolving Album Cover

- Ada on Ada: A Programmer’s Manifesto

- The Best Story I Ever Wrote, Annotated

- Skeuomorphic

- Graffiti and New Media

- Which Text(s) Work(s)?

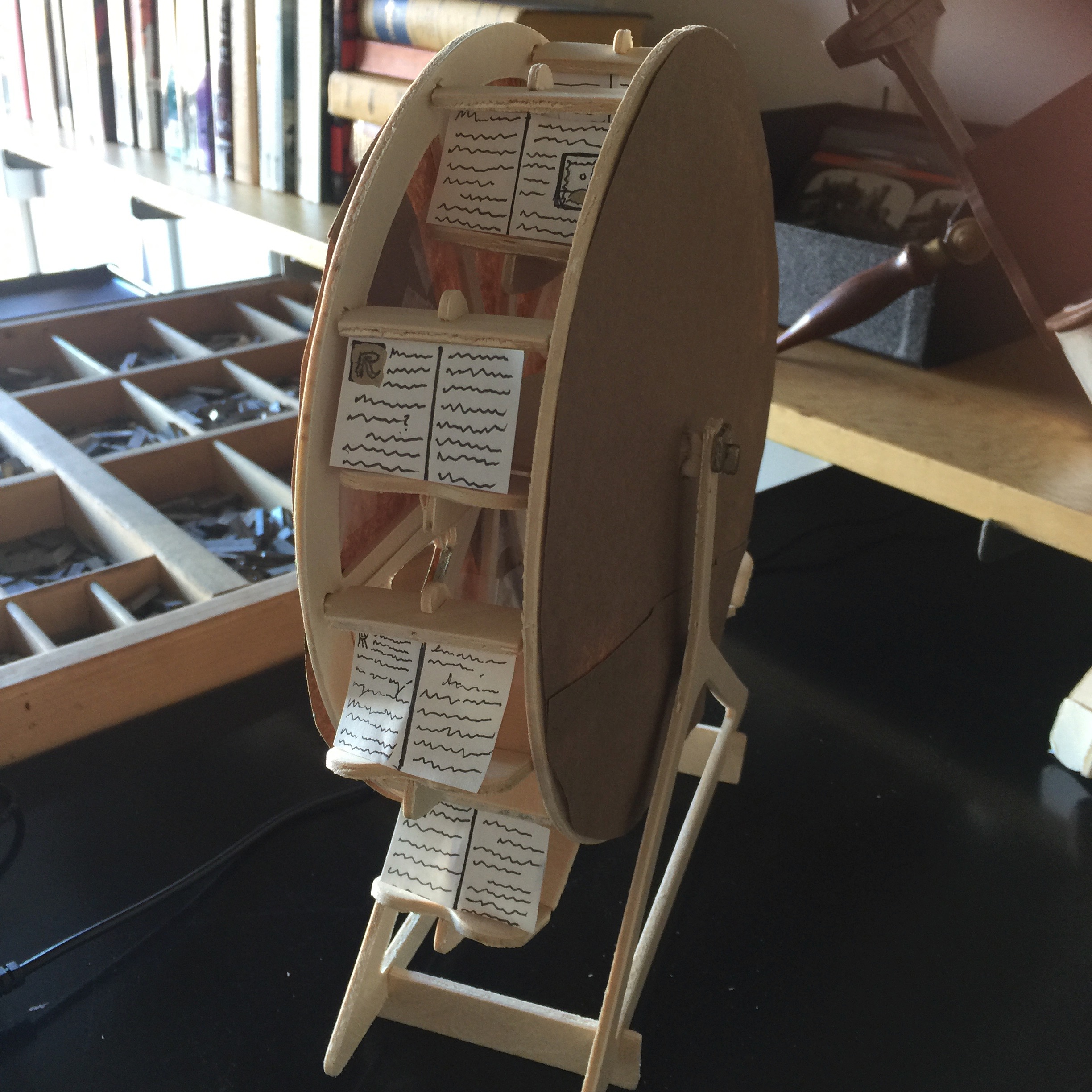

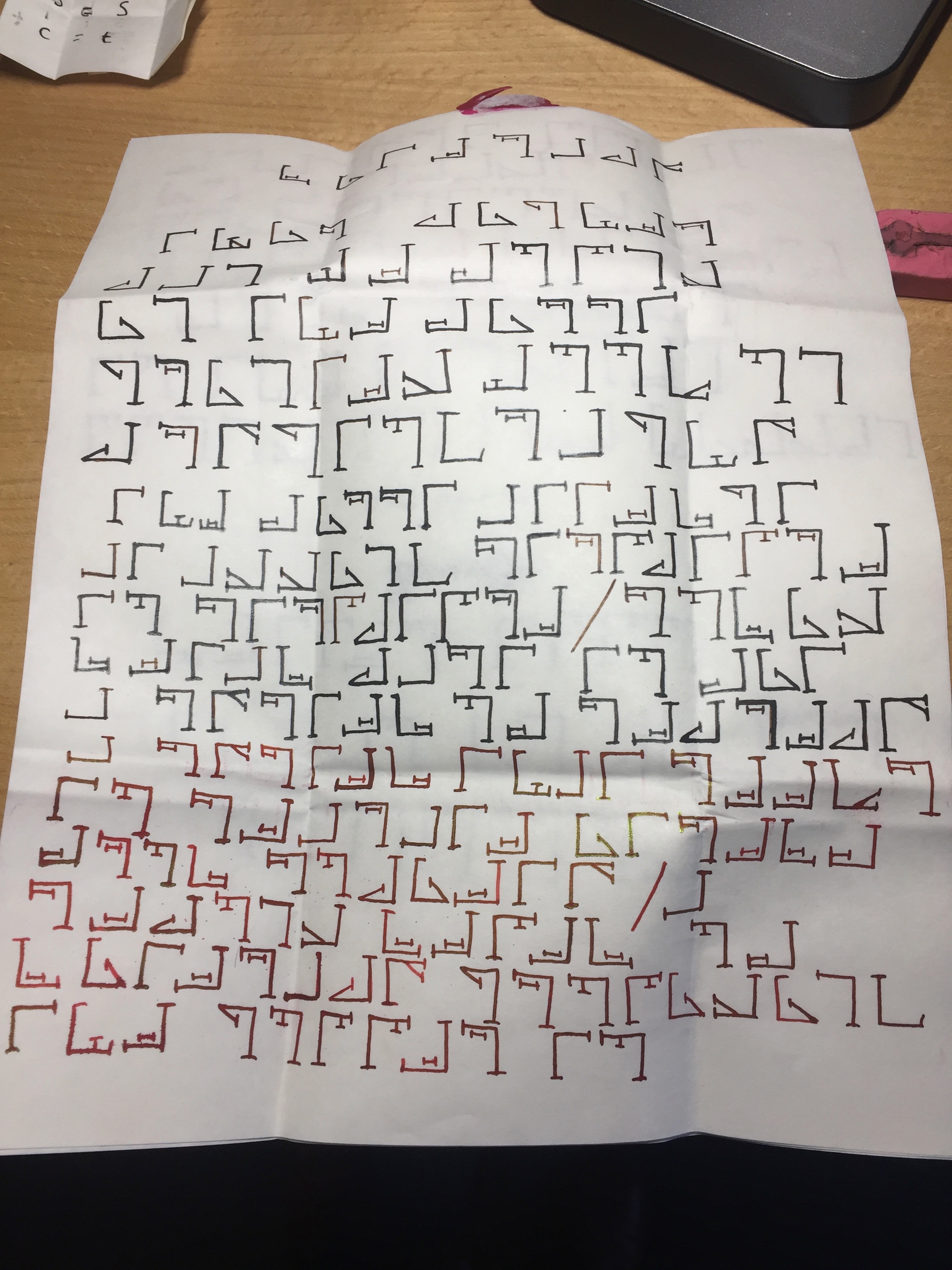

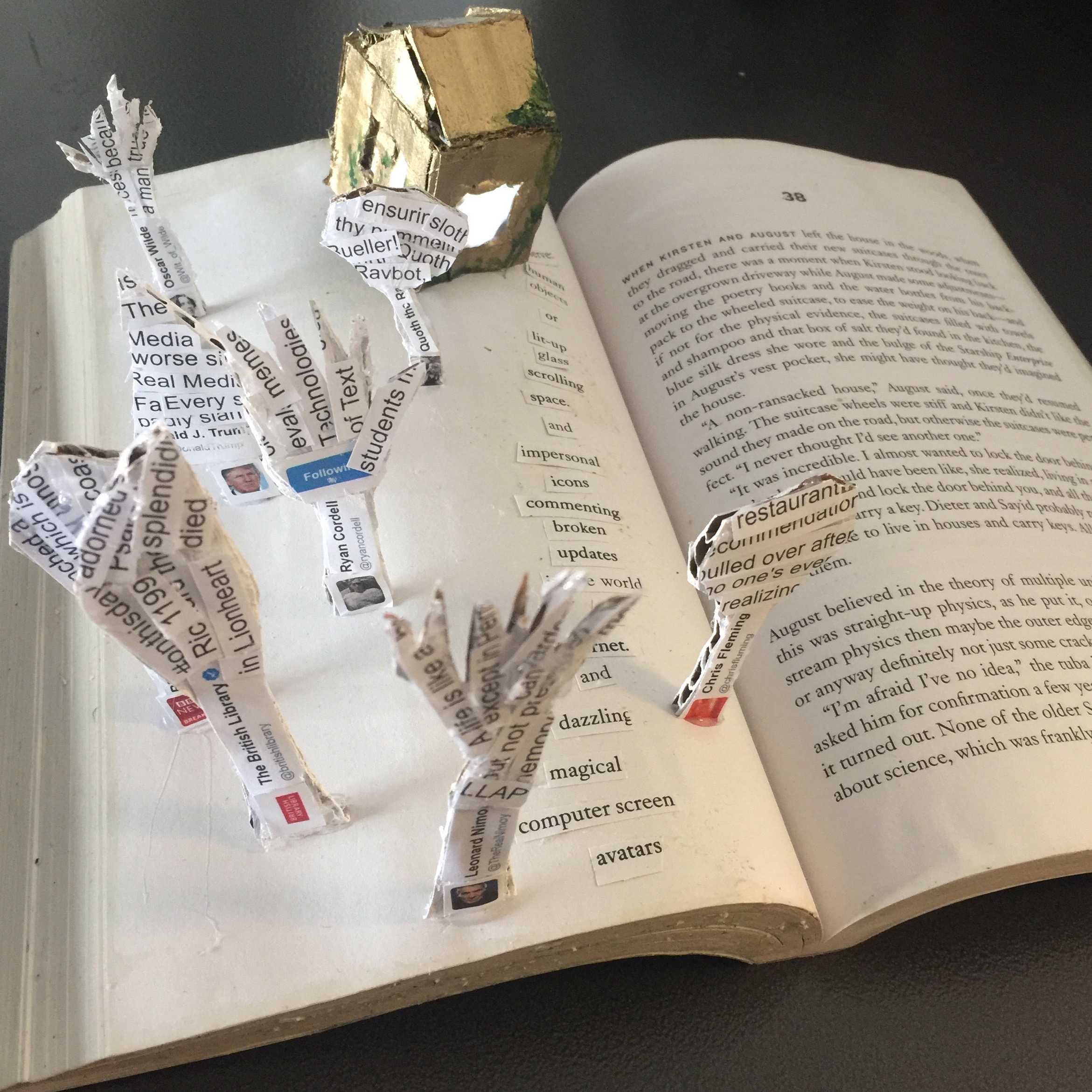

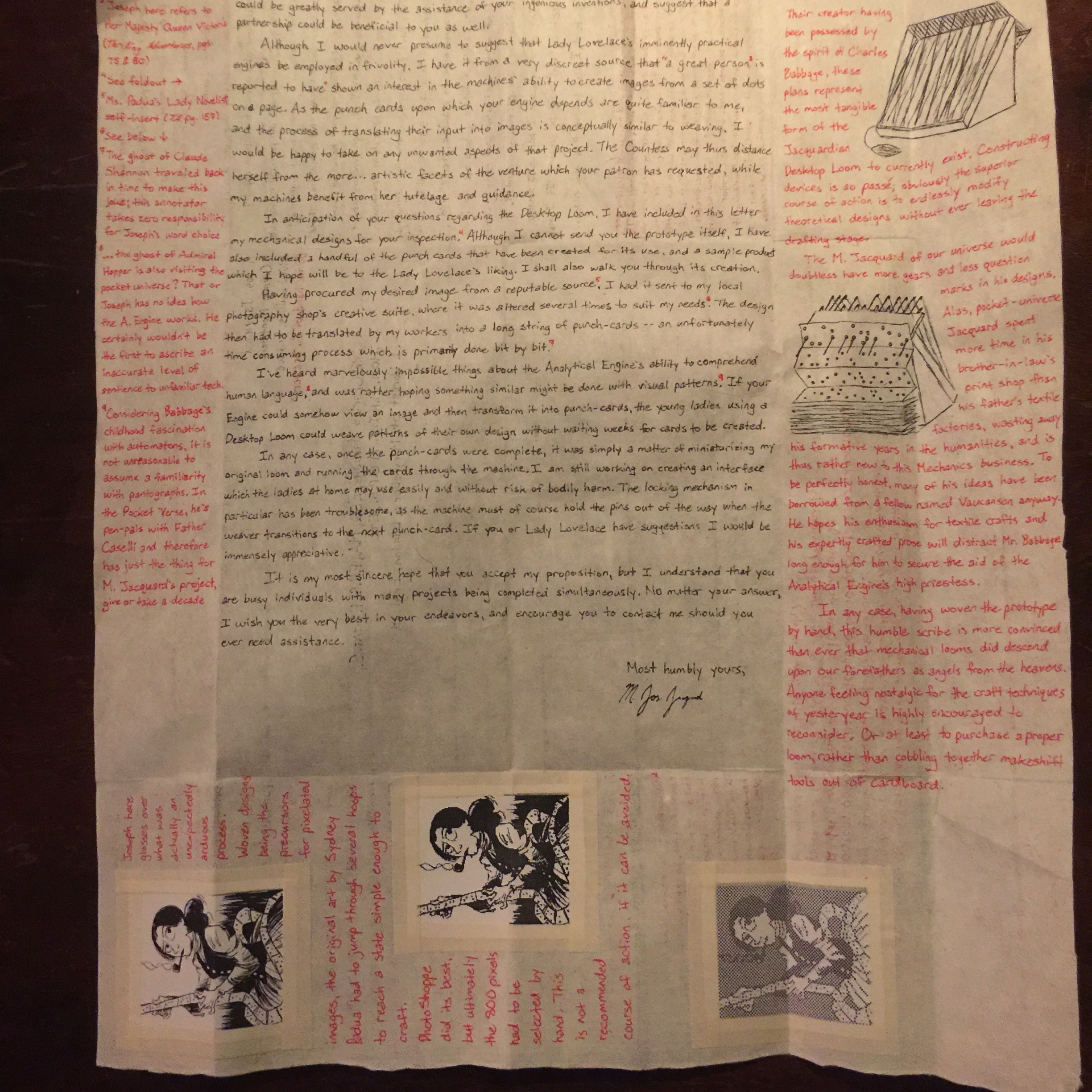

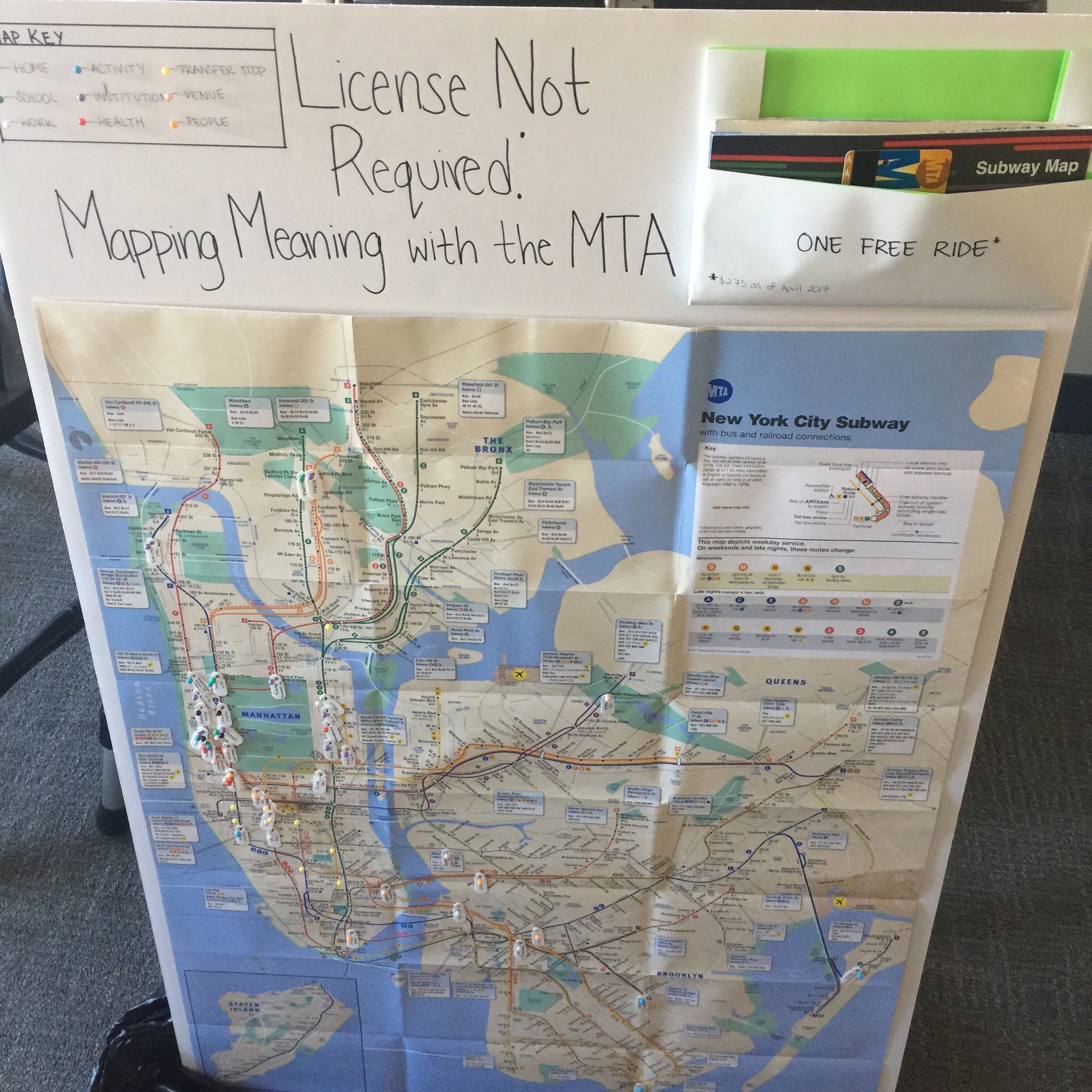

I have also added some pictures of some elements of physical unessays students have submitted. Most of these were accompanied by written components which I don’t reproduce here, but I’m happy to talk about them. I will bring these and some other physical model unessays to class to discuss, or you can peruse them during office hours.