Documentation and Preservation in (and of) the Codex

The Codex: Or, the Essence of Textual Preservation

The preservation of old printed books, or codexes, serves an inherently valuable purpose in the world of literature: it shows the very roots of the modern book, and modern practice of publishing, as we know them. The history contained within the pages of a codex (and even the history of the very material of those pages) set the precedent for what print could, and would, become. Mapping this history across various forms of the codex, therefore, can be incredibly illuminating in the similarities, differences, and contextual inferences we can draw from observation.

Such mapping can be applied to all aspects of the codex: how its paper was printed, what font the printer used, how the book is bound, and the types and forms of imagery pressed onto the pages.

Early Journalism via Illustration

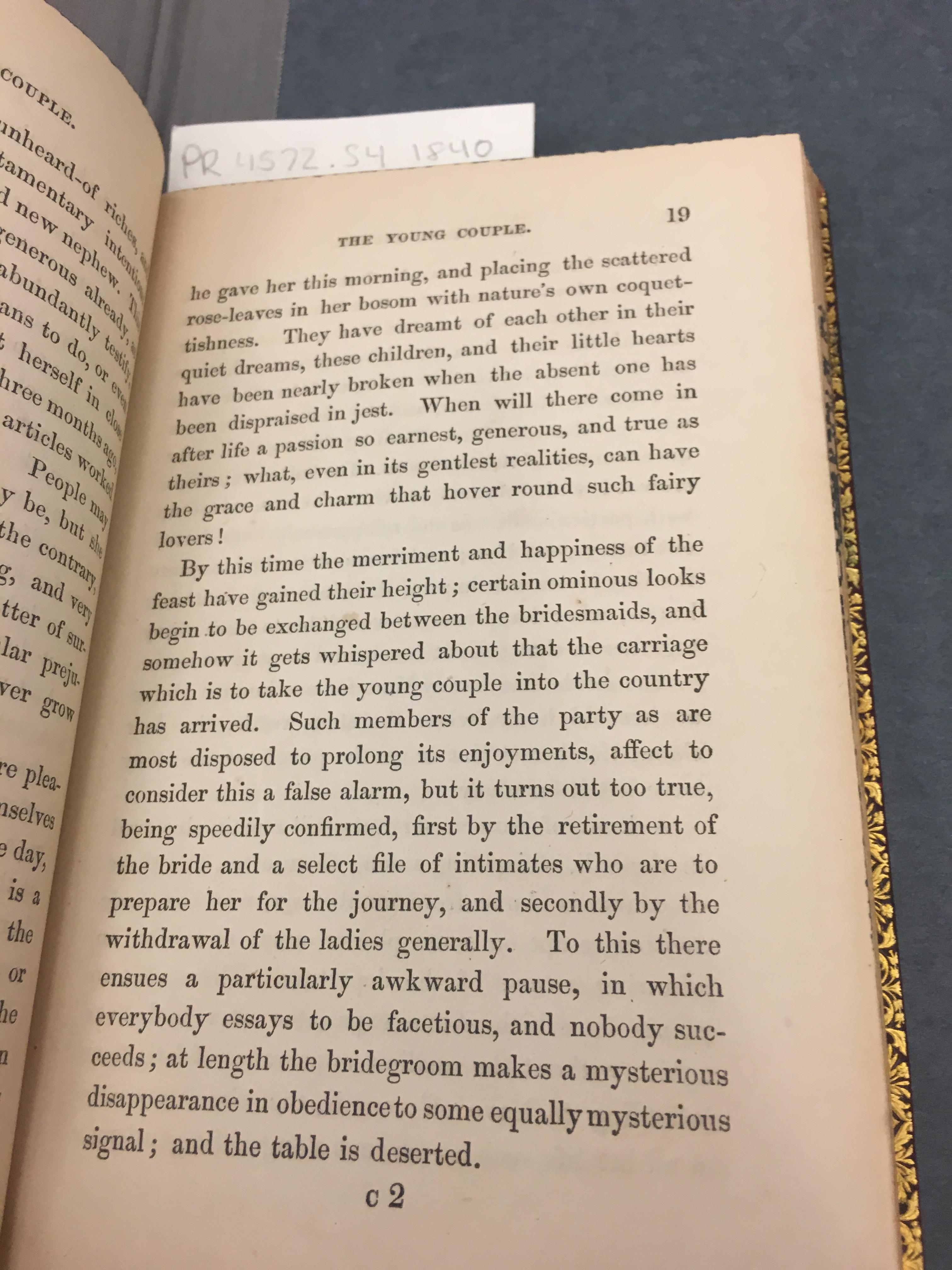

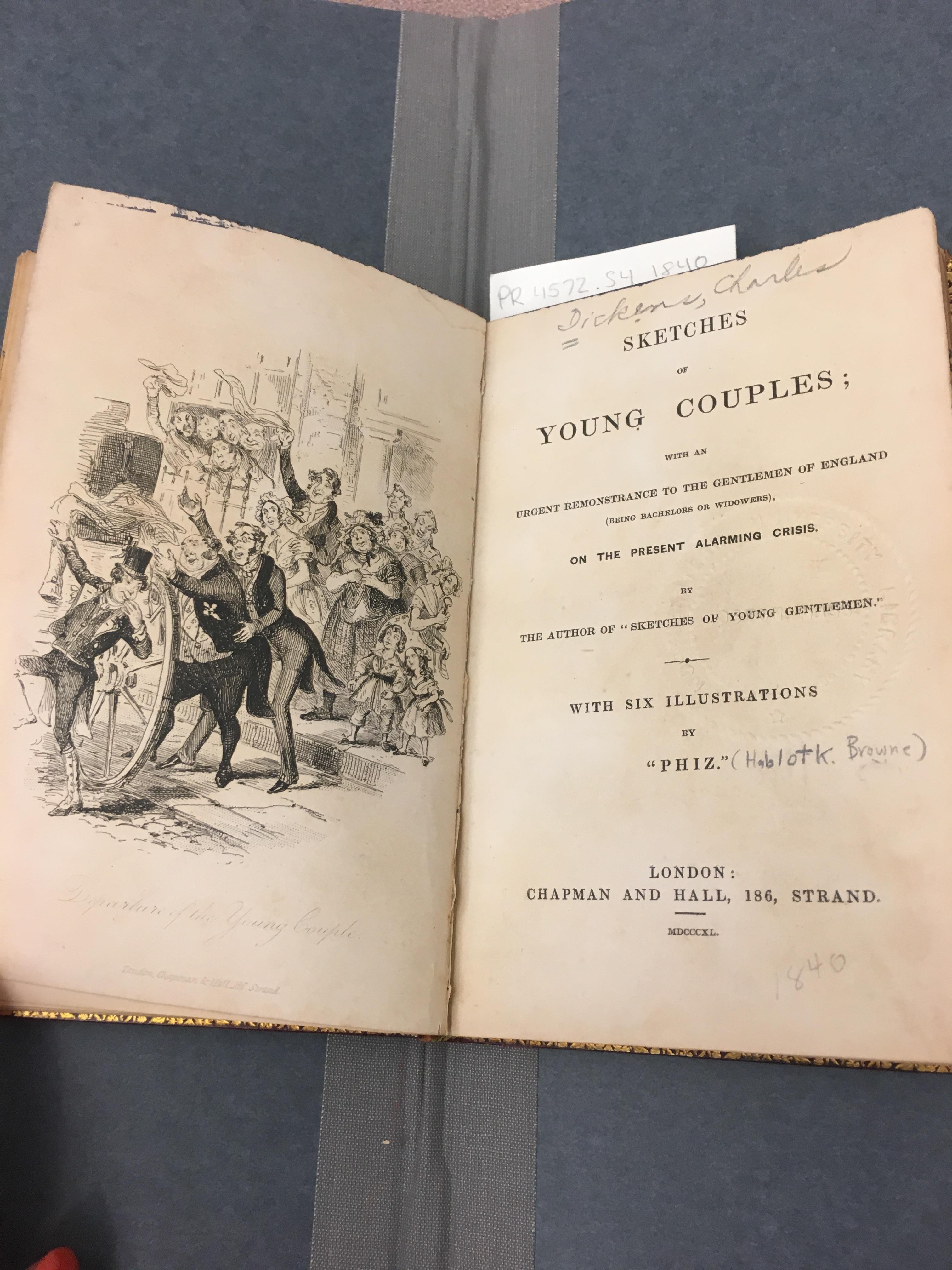

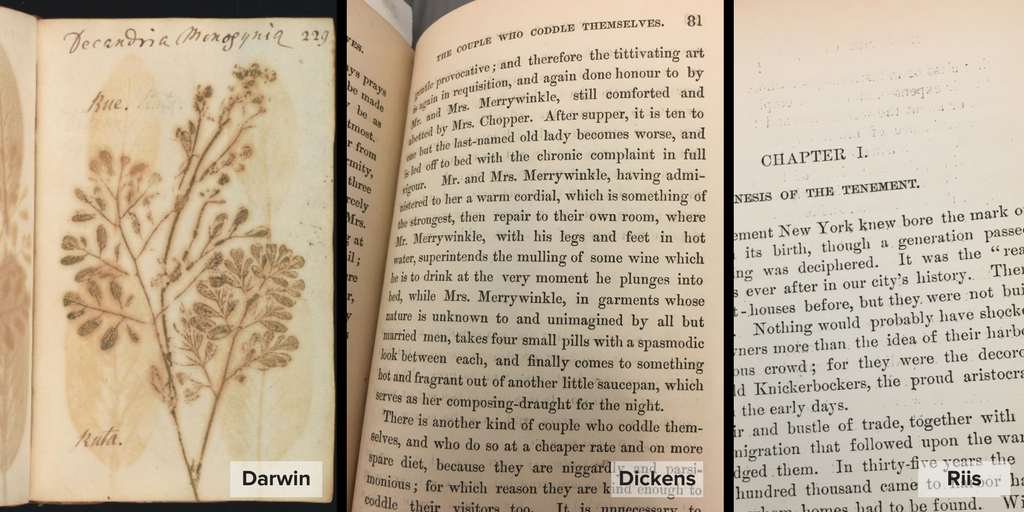

In 1840, Charles Dickens used a pen name to publish Sketches of Young Couples; with an Urgent Remonstrance to the Gentlemen of England (Being Bachelor or Widowers), on the Present Alarming Crisis.

This book, at first read of the name, seems like it would be a satire novel meant to poke fun at the conventions of courtship, marriage, and relationships during the 1800’s. The fact that it is seemingly making fun of social conventions, however, is no reason to discount Dickens’ work. In fact, it is argued to be an early form of journalism.

Dickens takes on this role of early journalist in 1840 to depict, through both description and actual illustration, the typical couples one would see in the 1800’s. Though the images in his book are all drawn, he claims that they represent actual people he has seen in the world. This methodology of documenting observation thus credits Sketches of Young Couples as early journalistic work.

The format of Dickens’ book is interesting to analyze. The book is relatively small and thin, which meant that it would have been easy to carry around with you. It was likely a mass-produced work, available to the common people as a form of entertainment and engagement with reading. The paper, which appears to be made from wood pulp, has aged to have a yellow tinge to it. The binding itself is traditionally threaded, and each section of pages is marked with a numbered, and lettered, signature. The signature only appears on the first two pages of the grouping, seen below as c2, with eight pages making up each group.

This book also features no official chapters - just sections titled after each of the types of couples Dickens is describing. The actual content of the book, then, is entirely focused on this description.

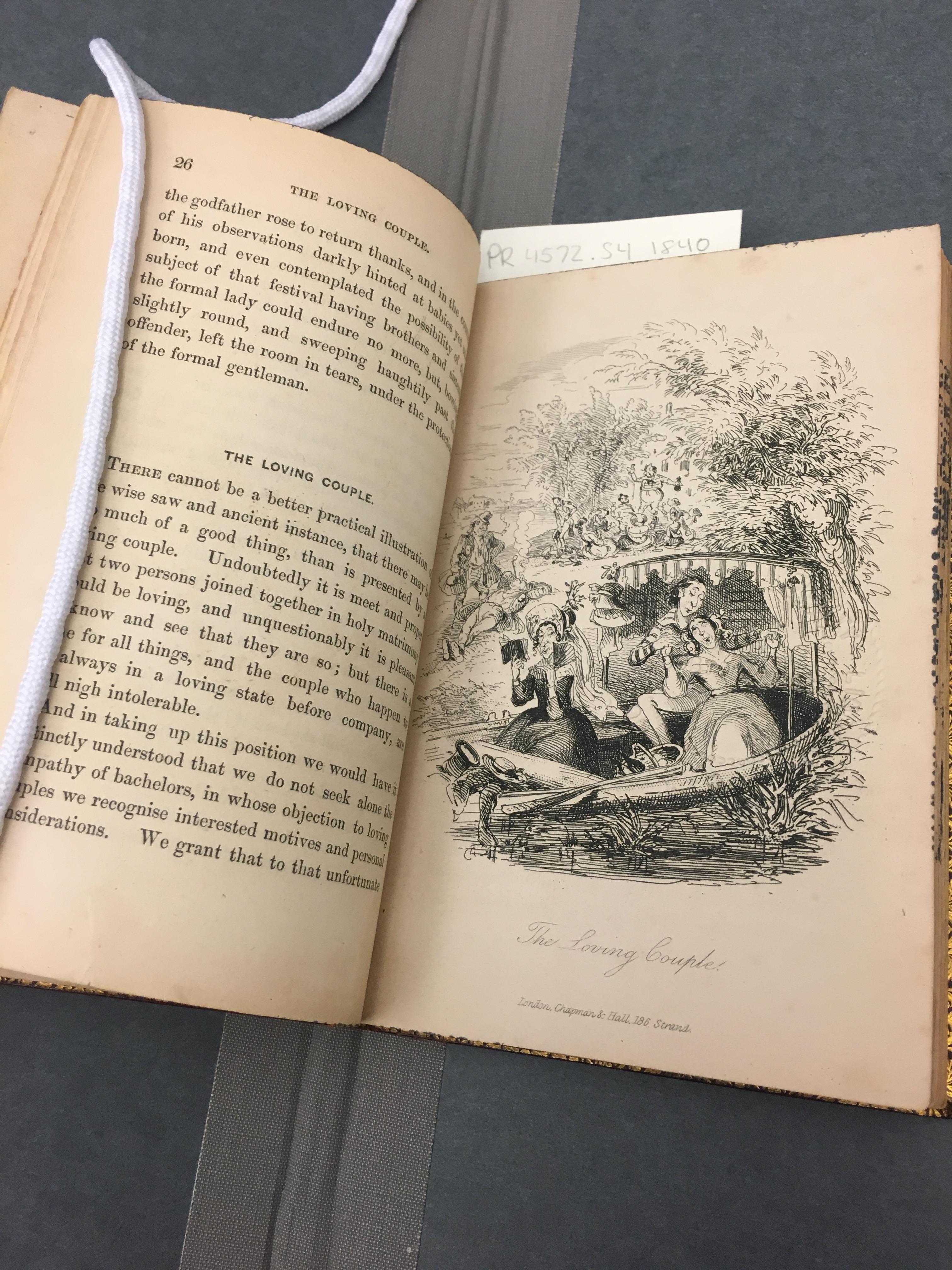

Dickinson describes 6 couples in his book, and each couple has an image created, meant to illustrate a real-life couple that Dickens is referring to. The first of these images appears directly adjacent to the title page.

The rest of the images featured throughout the work are placed next to the section where their description starts. These inserted images are worth close observation. Created out of the intaglio process of engraving, these images were printed on separate pieces of paper - much thicker than the paper the actual text was printed on - and have no page numbers or text printed on the back of them. It is clear, then, that they were inserted into the book after it was printed but before it was bound.

The descriptions below each image is straightforward - simply the name that Dickens has given the type of couple he is discussing. The full description of the couple is what comes from the actual content of the book.

Literary Journalism and Printed Photography

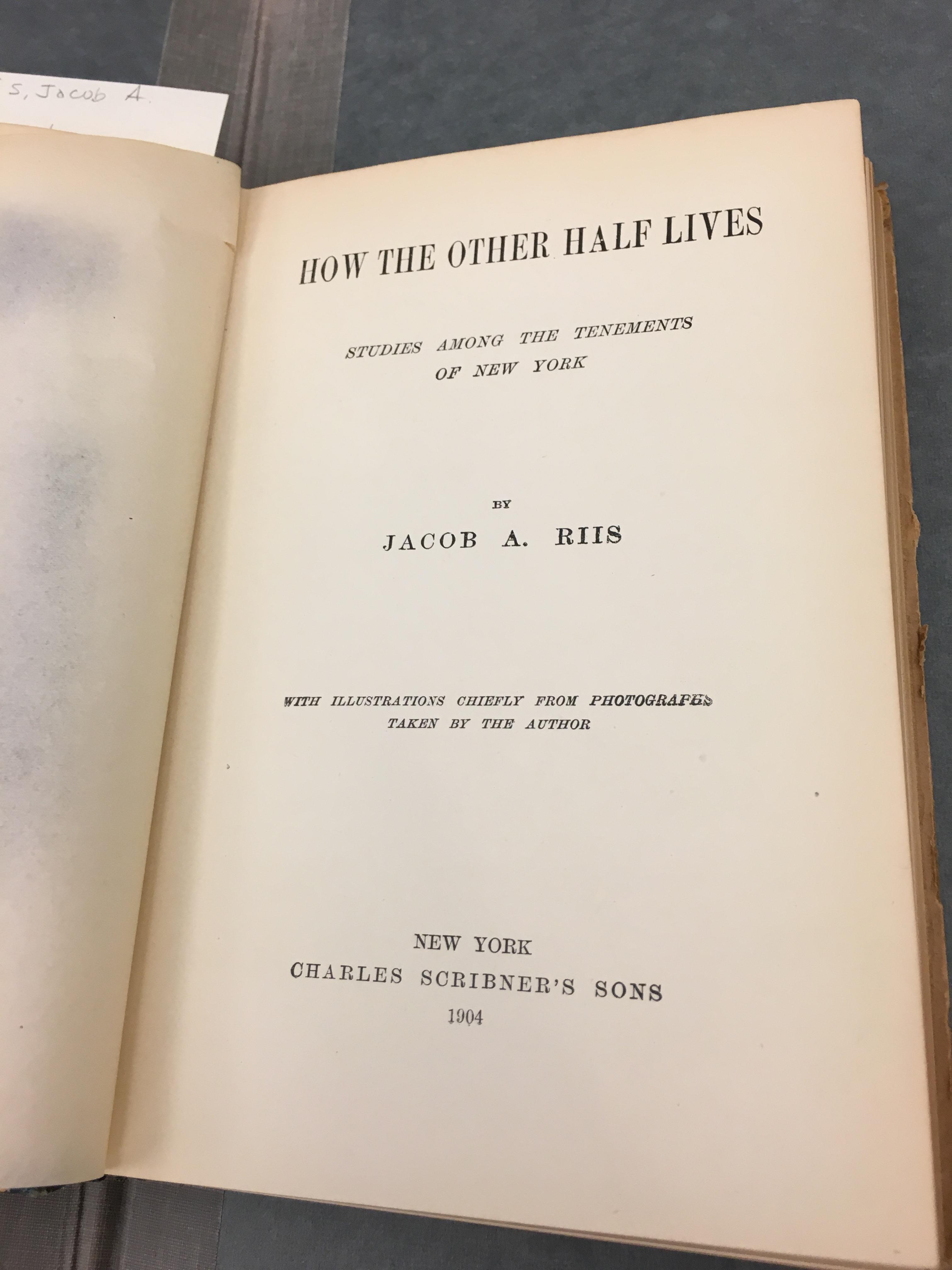

Published in 1904, Jacob A. Riis’ How the Other Half Lives is a startling depiction of what poverty was like in London during the the late 19th century. Created with the intention of showing the wealthy elites of the city what life was actually like for the lower class, Riis’ novel uses shocking statistics and artful imagery to paint a powerful picture.

Though it came out just over 50 years after Dickens’ work, these two books hold a number of similarities - and, more importantly, key differences.

Riis’ novel also begins with an illustration positioned adjacent to his title page, but with a thin sheet of acid-free tissue paper separating the image from the page of printed text.

This was likely done to prevent the ink from the image leaking onto the crisp and mostly white page of text beside it.

Though the paper Riis’ book is printed on was also not handmade, it has a thicker feel than Dickens’ that is consistent regardless of whether the page features images or text. The type in each book is also very similar, and was probably the standard font used for printing for some time as it was clear and easy to read.

While Dickens’ book was separated by sections, Riis’ is split into chapters, each dealing with a different issue throughout the city of London. How the Other Half Lives also features signatures to mark page groupings, but are represented by numbers, rather than a letter and a number. Due to the nature of this novel and the research Riis had to include, we also find footnotes throughout the work that reference to the statistics found in the book’s Appendix. One other key distinction of the works is the binding - Riis’ book, unlike Dicksens’ was glued rather than bound. This difference in binding shows a clear, traceable change in how books were produced that occurred in just a few decades.

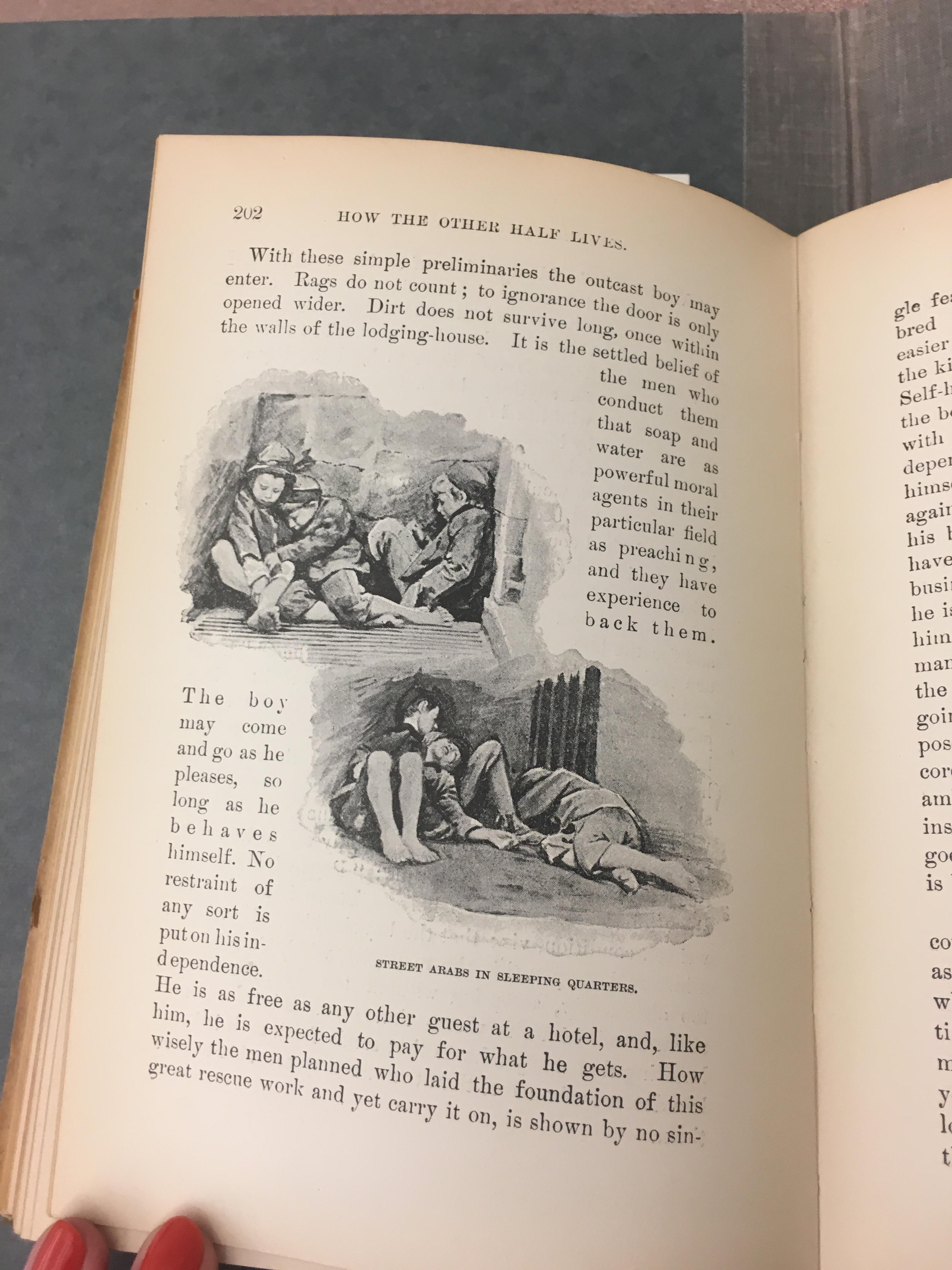

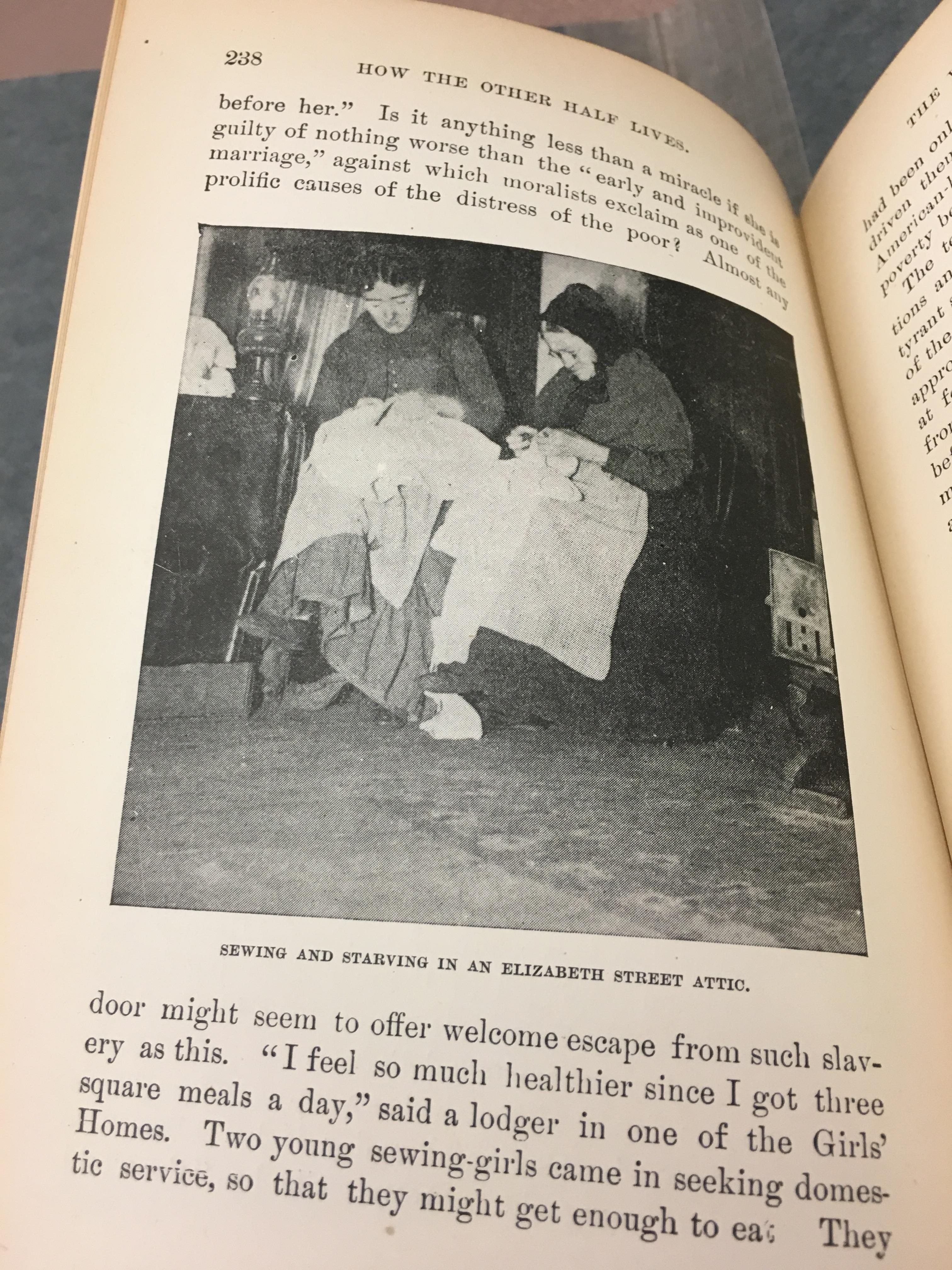

The most important difference between the books, however, is their use of images, as well as the types of image printing methods used. Riis’ book is one of the first forms to feature printed photographs, depicting real-life images that were taken and then reproduced via engraving for printing. It also, however, features a variety of woodcut and engraved images throughout its pages.

For Riis, these images are vital to telling the story of his text. They are found directly set along with the type, breaking up paragraphs of text, and taking up full-pages with their detail.

Rather than include the images later as a way to depict the descriptions being written, these images are integral and necessary for Riis’ book to be what it is. They flow as easily within the book as any other page would, and serve to enhance the bleak story he is telling.

Outside of the actual images themselves, the descriptions Riis provides further enhance their impact. While Dickens’ image captions were just their title, Riis uses captions like the one pictured below to really show his reader what life was like for the people in his photographs. The image, which features two women sitting together sewing, reads, “Sewing and Starving in an Elizabeth Street Attic.”

It’s clear that while Dickens’ work may have been read more as a tongue-in-cheek satire meant to amuse its reader, Riis’ was read less for pleasure, and more as an actual method for education, preservation of hisory, and learning.

“Printing” Nature

One century before Dickens or Riis ever put pen to paper, Charles Darwin was studying botany. In the late 18th century, he kept and maintained a small volume of his findings, depicting leaves and flowers in what is referred to as “nature printing.”

Darwin’s journal was surprisingly well-organized, and well-kept by his descendants. It was likely not accessible to many outside of Darwin’s personal circle until much after his death, when his findings were digitized and placed online for anyone to view (as I am doing now); a journal, even a scientific one, is a terribly personal thing.

Nonetheless, as a means for documentation, Darwin’s journal begins with an alphabetized index of all of the plant forms collected in his journal, with page numbers next to each name, much akin to the Table of Contents found in both Riis and Dickens’ works (not pictured).

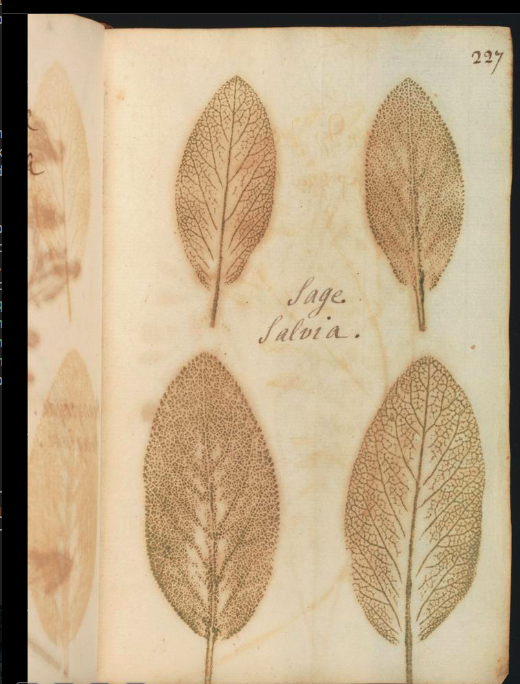

Clearly, as a journal, Darwin’s work is handwritten and not printed like the previous two books discussed. It does, however, feature print in a remarkable way - Darwin’s nature printing techniques. Defined as “a technique for making an impression directly from a plant by inking a flattened specimen and pressing the inked side onto paper,” nature printing allowed botanists like Darwin to preserve life-size, incredibly detailed, and accurate depictions of the plants and flowers they were looking at.

One of the more remarkable of his prints can be found on page 227 of Darwin’s journal depicting sage, showing every vein of the plant and even leaving behind impressions its very texture.

This level of detail can be likened, in fact, to both Riis’ photographs and Dickens’ engravings. Though they are closer in nature to the real-life depictions of the photograph, the intense detail of the pressed leaves is much akin to what can be seen in a well-done engraved illustration.

A problem with using ink, whether in print or in writing, is that it can transfer, or leak. This inherent problem can be seen in all three of the discussed texts, as illustrated below. For Darwin, previously-pressed leaves appeared to transfer onto the next page and form a shadow around another image. Dickens and Riis, however, have the problem of ink leaking through the thin paper of their works and leaving a backwards impression of text.

Documentation and Preservation in (and of) the Codex

All texts are a form of preservation of knowledge, in one way or another.

- For Dickens, that preservation was a satire about the very real forms of courtship at the time.

- For Darwin, it was documentation of his discoveries in the field of botany.

- For Riis, it was creating a narrative around the problem of poverty in London and its impact on both the city and the individuals living in destitute conditions.

The thing that makes the codex as a form of preservation so compelling, however, is that it functions as both a preservation of its content, and of its form at a particular point in the history of printing. Placing different texts in conversation with one another allows us to analyze not only the content itself, but the specific ways that content is presented, constructed, produced, and disseminated to the public. For the three above authors, their chosen form of putting ink to paper enables us to map the transformation of paper, image, and book production.

The codex as we understand it is the earliest form of printed books, though clearly not the earliest forms of the printed word. It ushered in a change in the social, political, and economic spheres of society where text became something you could (depending on your living means) go to the bookshop and buy.

In the same way that “written texts became objects of a new sort of interest” when written language was first gaining its roots, the codex became a new object of printed text that allowed for the lasting preservation of ideas, of literature, of imagery, and of history (Gleick, 35).

Thinking about the written word and the form of the codex puts Gleick and McLulhan into conversation in an interesting way. Though “the medium is the message,” “the written word is the mechanism by which we know we know what we know” (McLuhan, 9; Gleick, 29). In this case, the codex is the message, overflowing with a rich history of manuscripts and early printing, but the written word penned by Dickens, Riis, and Darwin allow us to understand the social and scientific contexts during the time that very medium was being created. Such thinking puts two inexplicably related ideas into conversation that link together both the written/printed word and the very thing it is written/printed on.

FIELDBOOKS · MODEL