Text throughout the centuries

Lab / Fieldbook 2

MFA Activity, Comparing Textual Artifacts

First Artifact

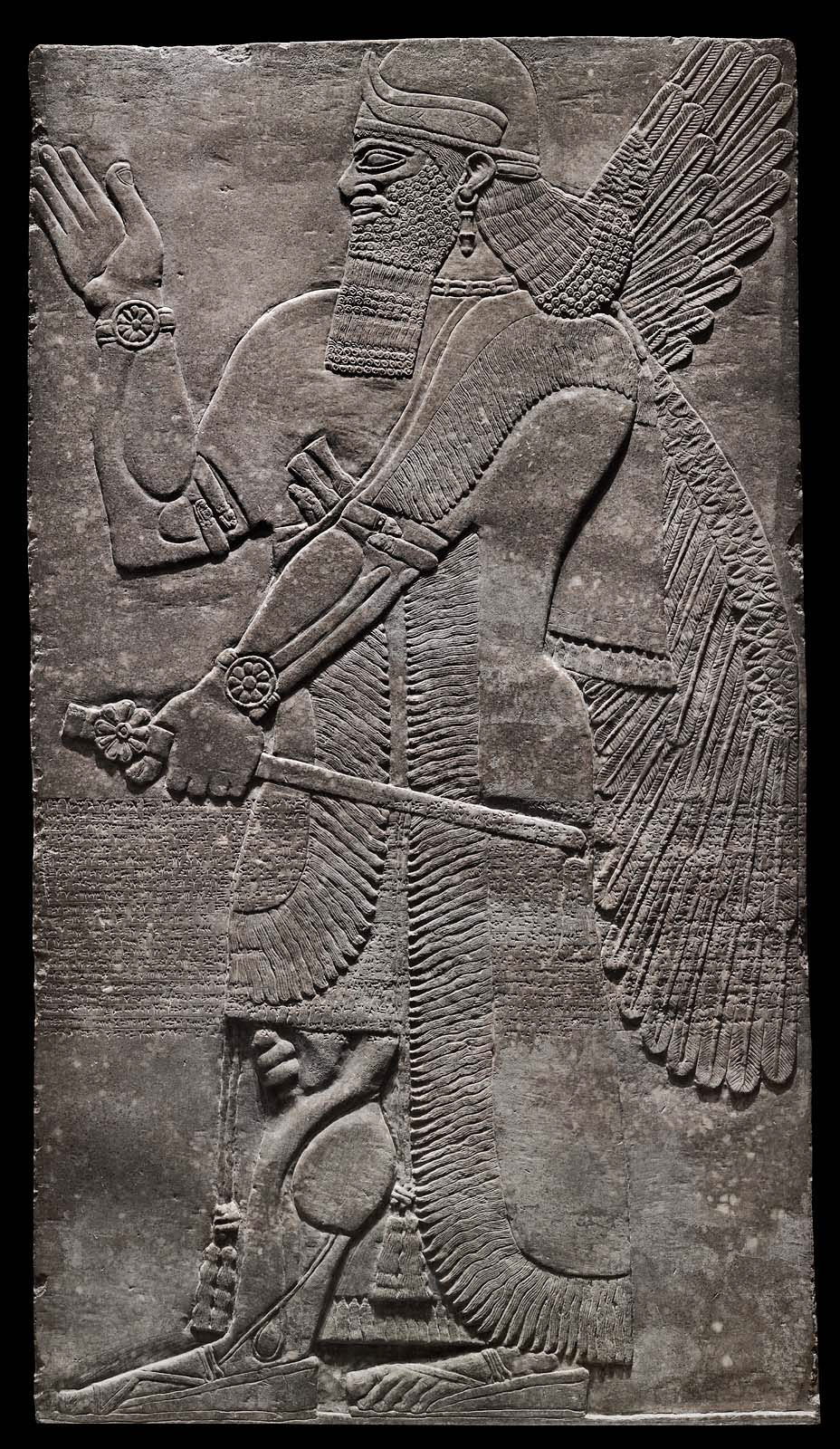

For my first artifact, I travelled about ten steps from the cuneiform tablet to this relief of a winged deity. The description said it was from Northern Iraq, specifically from the Northwest Palace of Calakh, of the Assyrian Empire under the reign of Assurnasirpal II, from 883-859 B.C. The description there said it was made out of alabaster, a form of gypsum.

This artifact caught my eye for several reasons. It was one of the biggest artifacts in the room, while everything else– including the cuneiform, was small and either fragmented or very worn/faded. I marveled at how it was still in great shape. When I got closer to look at the detail, I was surprised to see the inscriptions. Here’s a closer view of them.

This was another artifact with cuneiform script! I had seen these symbols in the Gleick reading, so I was really excited that I knew what they were. I knew that the script on the large tablet must hold lines and lines of information, whether it was just business records or a historical account. A translation on an adjacent placard revealed that it was about Assurnasirpal II and his reign. The placard also revealed that that Assyrians surrounded themselves with images of fantastic deities like this. The images of the deities were supposed to keep the king from harm. Below is an excerpt from the translation.

“Palace of Assurnasirpal… king of the world, king of Assyria; the valiant hero, who goes hither and yon, trusting in Assur his lord and who is without rival among the princes of the four quarters; the shepherd of the fertile pastures, who fears no opposition; the mighty flood, who has no opponent; the strong man who treads on the necks of his foes, who crushes all his enemies…”

Evidently, this cuneiform is wholly dedicated to Assurnasirpal. Not only was this intricate and elaborate relief created to protect him, but it was also created to trumpet his achievements and his greatness. This is especially notable, because the Gleick reading stated that cuneiform had originally been used for clerical purposes, as stated on page 42.

“When scholars did learn to read the Uruk tablets, they found them to be, in their own way, humdrum: civic memoranda, contracts and laws, and receipts and bills for barely, livestock, oil, reed mats, and pottery. Nothing like poetry or literature appeared in cuneiform for hundreds of years to come.”

We see the evolution of cuneiform here. What was once used to denote everyday records evolved to record and herald the complex accomplishments of great kings in history, such as Assurnasirpal. While the pointed and wedge-y physical appearance of cuneiform remained much the same for centuries, this artifact helped me understand and visualize how the purpose of text can change so much over time.

Another thing that was noteworthy about this artifact was that even though it is nearly three thousand years old, it is still in remarkable shape. That is the reason I took a closer look at it in the first place. I did some research and found that alabaster is a soft mineral that was often carved into ornaments. I could see why whoever made this used alabaster. As I mentioned above, many of the other artifacts with inscriptions were made out of clay. While clay would have been very easy to carve inscriptions into, the poor state of the clay artifacts was a testament to its low quality. Whoever made this knew exactly what they were doing. They wanted the great Assurnasirpal to be remembered forever, and making the relief out of clay would not have accomplished that. Clay was for recording simple and less important information, while more premium materials like alabaster were used to record the important things, like something that would both proclaim a mighty king’s reign and protect that same king from evil.

Second Artifact

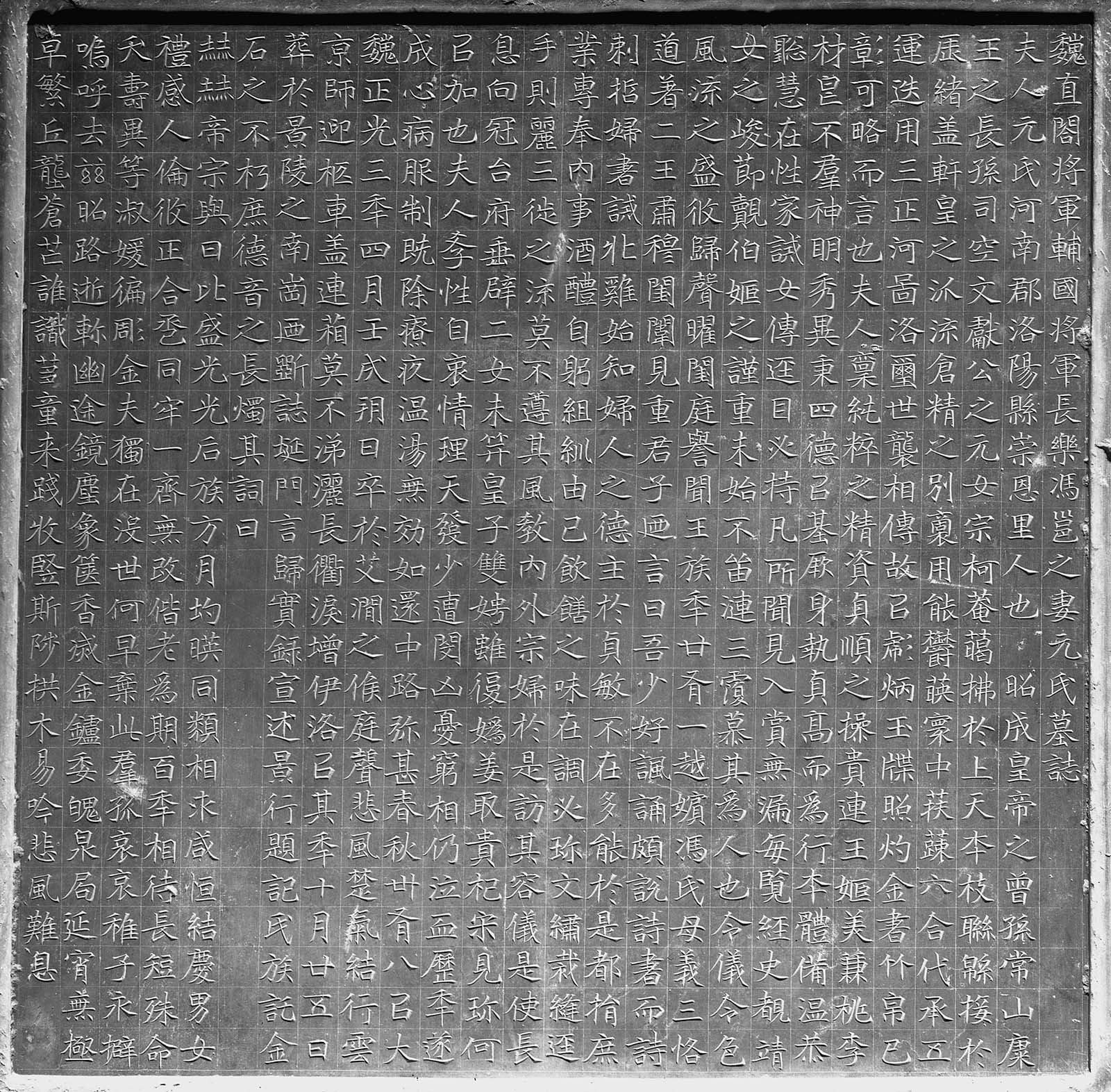

My second artifact was this epitaph tablet for Lady Yuan, who was one of the daughters of an ancient Chinese warlord Yuan Shu. The placard said the tablet was from the Northern Wei dynasty, specifically from A.D. 522. It is a square limestone block with four incised mythical figures on the four sides.

Now, I am Korean, but I learned to read many of the basic Chinese characters. I was surprised to realize that I recognized several of the characters on the tablet. What surprised me was that the modern-day Chinese characters I had learned were exactly the same as the characters from well over a thousand years ago. I was even more surprised when a staff member, who was Chinese, approached me and explained– and thus confirmed– that the characters were exactly the same now as they were then in A.D. 522. This meant, of course, that they both looked the same and meant the same throughout all the years.

This contrasted sharply with the Assyrian relief. While the cuneiform looked the same, its purpose and meaning changed completely over the centuries. On the other hand, the engraved Chinese calligraphy not only looked the same, but also had the same purpose and the same meanings over the centuries. It boggled my mind that something could be so consistent over such a long period of time. The staff member had no trouble quickly reading the characters and briefly telling me about Lady Yuan. On the other hand, only a team of the most experienced scholars and historians must have been able to translate the Assyrian relief. Even they must have taken several years to do so. It just amazed me that two different text systems could evolve in such different ways. While both didn’t change much (or at all) in physical appearance, their purposes changed greatly. The cuneiform started off as a numeric system, and eventually became its own thing apart from pictographs and an alphabet to record the same type of historical record that the Chinese inscription did.

Third Artifact

I wanted to focus on something different for my third and final artifact. I went to the Ancient Greek exhibit, and found exactly what I was looking for, a painted oil flask from Ancient Greece, specifically, from about 450 - 440 B.C.

This artifact was intriguing for several reasons. It was different and similar to the two previous artifacts. It was similar in that there was text on it. The text, which was Ancient Greek, said that “Alkimachos, son of Epicharos is handsome.” And we know there are some differnces between Ancient and modern Greek. But that is not the important “textual” feature of this artifact. The picture on the jar was the “text.” It told the story of the death of Orpheus.

Here is a close-up of the gruesome scene.

I found it intriguing that this artifact conveyed its message through the painting. What’s more, this oil jar was actually something that people could use. Sure, one could argue that the Assyrian relief was used to protect the king, but even then, the physical relief itself wasn’t a tool. Nor was the Chinese tablet. On the other hand, people could definitely use this jar to store oil it. The jar not only told a story, but it also was also used both pratically and decoratively. Examining and analyzing this artifact helped me realize that textual objects weren’t always about texts. Images, or any medium, for that matter, could be text– the message.

Final Reflections

One thing that was similar about all of these was that they were obviously intended for the upper class in each of their respective societies. The middle and lower classes would not have been able to afford the luxury of these items, nor would they have needed such luxury anyway. If working Assyrians needed to inscribe something, they would have used clay tablets– if they could even write. Simiarly, even many people in modern day China are illerate, so there were probably very few common people back then who were literate. Finally, the poor in Ancient Greece would not have gotten such luxurious oil jars. They would have gotten more practical jars, jars that were only made to hold oil, and not tell a story like the one above. All of this reflects how text, whatever form it was in, was too often inaccessible to those who were not in the royal or upper classes. This trend continued for thousands and thousands of years, as we can see with the different eras from which these three artifacts are from.

FIELDBOOKS