Letterpress Printing, Negative Space, and Feminism: A History

The Trials and Tribulations of Compositing

There were two key takeaways from this past week’s in-class labs:

- Compositing is hard (like, really hard) and I never would have lasted longer than a single afternoon as a compositor in a print house.

- The amount of measurement, physical labor, trial and error, and other behind-the-scenes tasks involved in just the compositing and setting of type is severely overlooked.

In my last fieldbook post, I wrote at length about the perceived monotony of compositing. While I do still think that, for someone who is trained and so skilled in the work that they don’t even have to look at the font case to find the sorts they need, it does still ring true that there may have been a sense of monotony in the task. That monotony, however, is usurped by the sheer amount of mental and physical labor involved in the process.

With compositing and setting type, everything is a manual, mechanical, physical process. Your body and your mind are constantly engaged; for the compositor in particular, “whose busy fingers and absorbed look show her to be wholly engrossed in her work,” there is an intense amount of focus necessary to be successful (“Ramble,” 270). That focus stretches far past just the individual letters themselves to encompass one of the most important parts of compositing and printing: the blank spaces.

“I’ve Got a Blank Space, Baby”

To understand letterpress printing, imagine that every letter you see on your screen is an object, a tiny piece of metal. Not only is every letter an object, but every space between every letter is also an object. Every space between words, every space between lines—every bit of white space is an object. When typesetting, a printer has to think about negative space as something tangible (Lynch).

One of the most challenging parts of composing our printing project was, in reference to the quote above, the glaring presence and physical nature of the blank space. (Spoiler: this is, indeed, a link to a Taylor Swift song.)

From the various widths and lengths of leading, to the different sizes of en and em-spaces between letters, to the furniture used to hold the type in the place for actual printing - negative space was a salient issue for our print job, and one that was constantly in our direct line of sight that was still, at times, overlooked. When actually printed, all of the work that we put into the blank spaces was “never seen, but without it, everything printed would be nonsense” (Lynch).

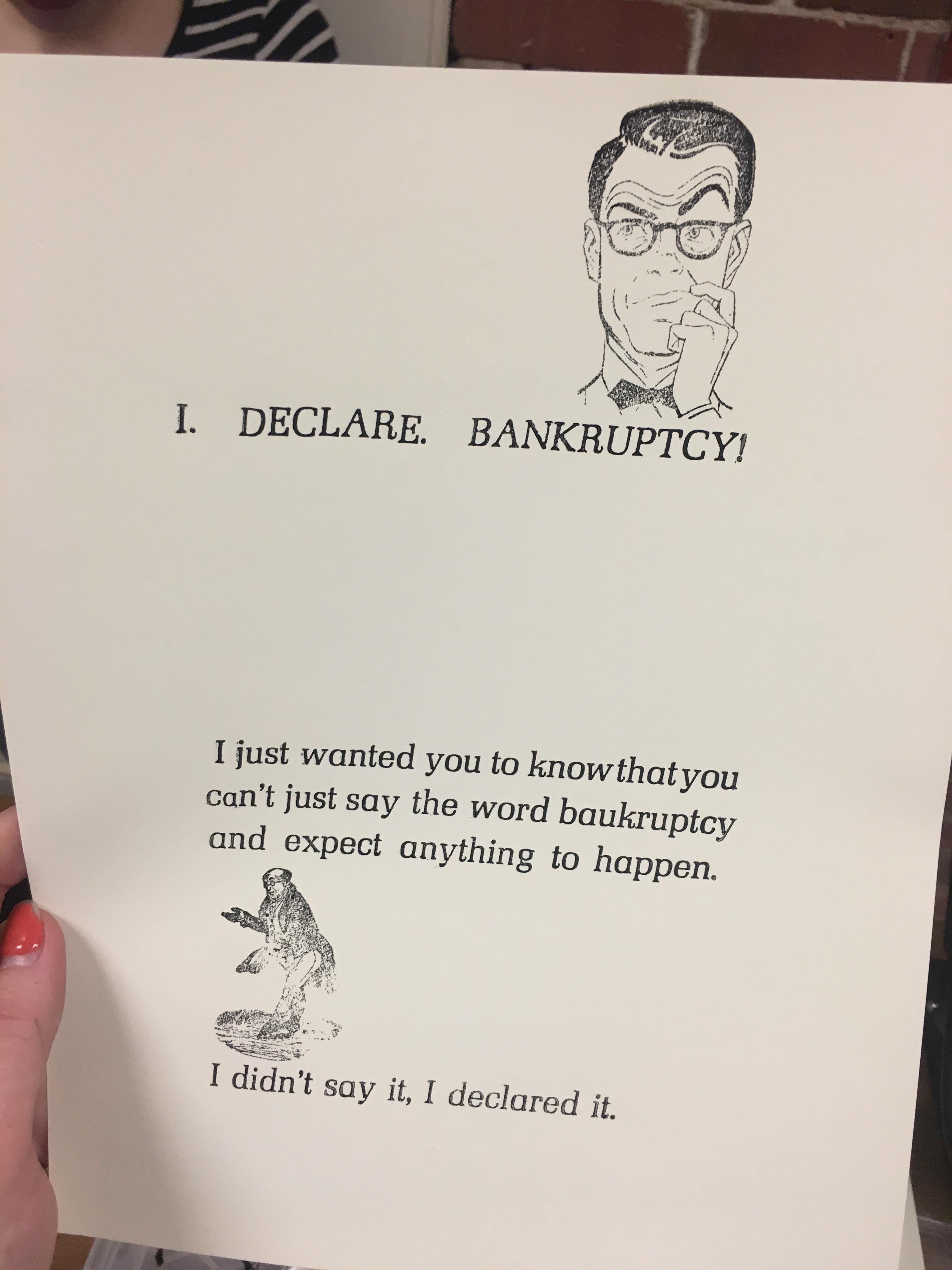

Blank spaces within our individual lines of type, as well as between them, had profound effects on the final product (pictured below). It’s clear that not actively considering the physical presence of negative space impacted the way that our type printed. The spaces between each line are vastly different, and the phrase “know that you” is spaced so closely, it looks like one word.

Our print also featured a typo from a misplaced “u” in a spot meant for an “n,” which further illustrates the difficulty behind compositing.

The “blanks” of the printing world are, arguably, its most important aspects. Without the blanks, print is illegible, would fall out of its arrangement and pie, and would, likely, not exist in the same way today.

This idea rings true of both the physical act of composing and printing, but also of the history of print itself - particularly in relation to women’s role in it.

The Victoria Press: A Feminist Print House

Reading about the Victoria Press established by Emily Faithfull, I can’t help but wonder what Benjamin Franklin’s all-male world of printing would have thought of the female-lead and operated house, “you women and girls sitting or standing before [compositors’ cases], busy working, some with the easy and rapidity of skilled compositors, some with the slowness caution of the half-trained workwoman, and others just learning their alphabet” (“Ramble,” 270).

Though many in the male-dominated field protested the continued existence of Faithfull’s print house, there is an inherent contradiction in its history that is worth unpacking. In particular, the idea of women’s work, and the inherent devaluation of gendered occupations when chiefly employing women.

The article, “A Ramble with Mrs. Grundy” makes particular note to state:

“The compositor’s trade should be in the hands of women only. They are eminently suited to it, and it is eminently suited to them. To men belong the imposition and press-work” (271).

At this point in the article, we are able to see the clear distinction between roles in the printing house, and the idea of where women’s place was. There is something to be said of the fact that Faithfull, having started the Victoria Press, only employed women compositors. On the other side of the same coin, however, it is vital to understand the idea of compositing as “women’s work,” and the damage that could occur to the profession as a result of a patriarchal society (272).

Despite this, we should read Faithfull’s work and the work of the Victoria Press as an early feminist venture into a field that was, at the time, completely owned and operated by men. By using their own physicality, particularly their smaller fingers, as a way to brand compositing as “for women,” Faithfull and her compositors were able to succeed and scale their printing house irrespective of gender.

FIELDBOOKS