Simulating the Scriptorium

Simulating the Scriptorium & the Qur’an: From Revelation to Preservation

The Qur’an, much like the Bible in Christianity or the Torah in Judaism, is the holy text that informs Islam. It is written in Arabic and is said to have been revealed to the Muslim prophet Muhammad over a span of 23 years – from 610 to 632 CE. The Qur’an contains 114 chapters called “Surahs,” 86 of which were revealed during the prophet’s time in Mecca, and 28 that were revealed during his time in Medina, cities of present day Saudi Arabia. According to Islamic scholars, each religious prophet brought to their society what was culturally valued in order to gain credibility within their community. Moses brought magic to a people fascinated with sorcery. Jesus brought the ability to heal to a community suffering from illnesses. Muhammad is said to have brought poetry to a people fascinated with language. Islam’s appeal to Arabia is thought to stem from the Qur’an itself.

Context

Before the Qur’an was revealed to Muhammad through Angel Gabriel (Jibril in Arabic), the people of Arabia were known to write or commit poems to memory to compete in public competitions – equivalent to what might be a modern-day rap battle. An oral and auditory fascination with the poetics of language placed an emphasis on memorization over textual media within Arabian society. When Muhammad first received revelations of the Qu’ran (documented as Surah Al’ Ala), he only shared the verses with his wife Khadija, and later close friends. When Islam began to grow within the community, what prompted several people to convert to Islam was the poetry of the Qur’an itself and the message it carried. Members accepted the scripture as divine because they did not think Muhammad, an illiterate man orphaned at a young age, was capable of producing the kind of sophisticated Arabic used in Arabic.

Compilation & Organization

The compilation of the Qur’an as a text is a process that extends from during Muhammad’s lifetime to years after his death. The following list briefly outlines the different stages of the development of the Qur’an as a formal text.

- In the lifetime of the Prophet: Memorization by the Companions

- During and after Muhammad’s life: on writing materials (Suhuf)

- In the time of Abu Bakr: Manuscripts(Mushaf)

- In the time of Usmaan: The Book (Qitab)

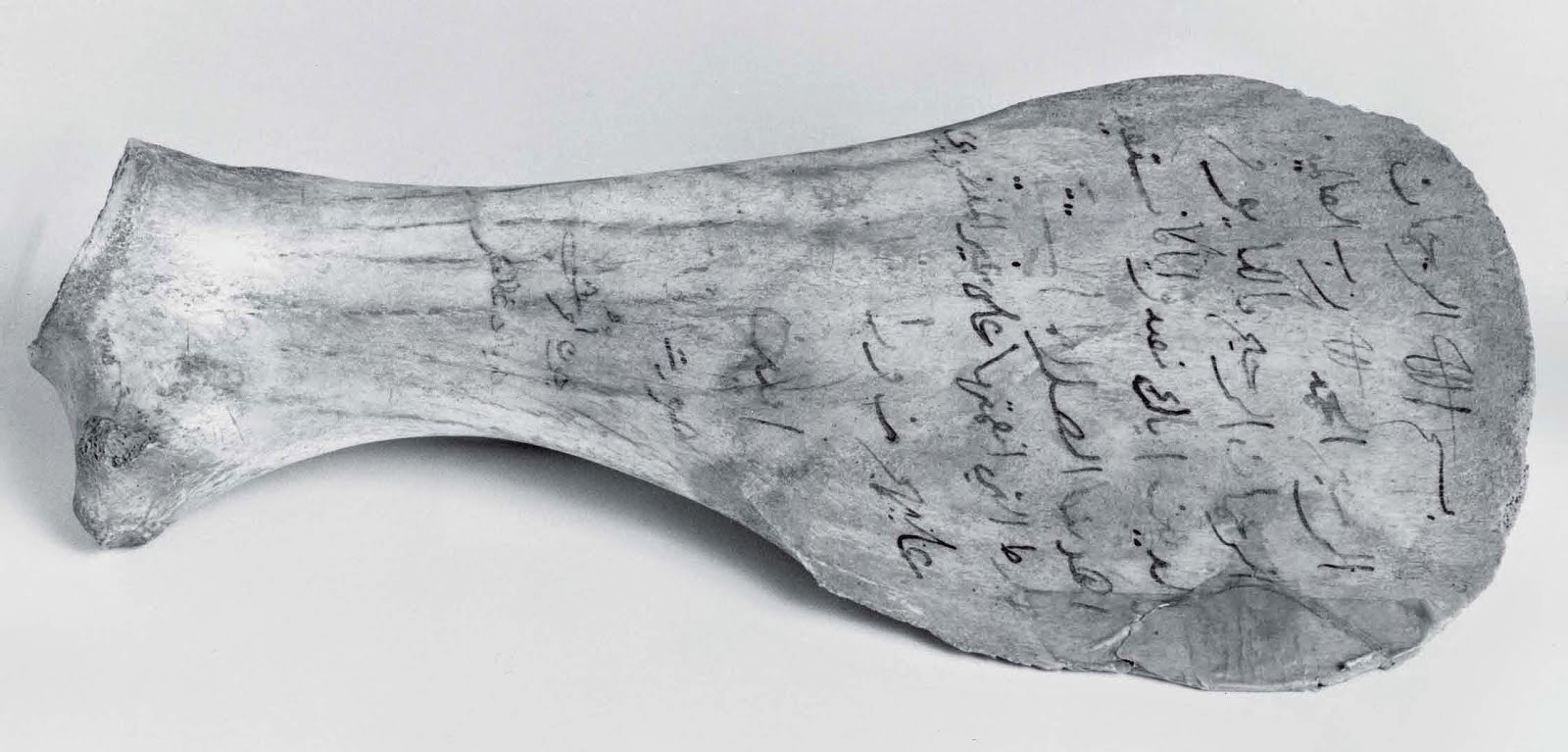

The Qur’an in book form did not exist during the lifetime of Muhammad. As Islam grew, the chapters of the Qur’an were memorized as they were revealed over 23 years. As the prophet received revelations, he would commit Surahs to memory and recite them to Companions who would in turn commit the verses to memory. People who memorized the Qur’an by heart were formally known as “hafiz.” In addition, scribes would write the verses on different materials such as papyrus, cloth, leather, or bones (3). The word for these loose pieces of writing material, or “suhuf” in Arabic, is referred in the Qur’an itself (Al-Ala 87:19). At other times, the Qur’an refers to itself as “al-Qitab,” or “the book.” Below are a few examples as to what “suhuf” might have looked like.

Animal Skin:

Animal Bone:

At the University of Birmingham, recent carbon-dating of a Qur’an manuscript fragment dates the artifact to somewhere between 568 and 645 CE – contemporary with the life of Muhammad. Critics have argued that carbon-dating provides a reasonably accurate assessment on the date of an artifact’s medium – animal skin or bone – but that the date of the writing itself is more uncertain.

Academic historians of early Islam note that what is debated is not the existence of Qur’anic manuscripts, but rather the timing of their compilation:

“Reasonably sure that the Quran is a collection of utterances that [Muhammad] made in the belief that they had been revealed to him by God … [He] is not responsible for the arrangement… They were collected after his death—how long after is controversial.”

Islamic scholars mainly agree that the Qur’an as a book was not compiled until after the death of Muhammad. However, within the community it is generally agreed that the formal compilation of the Qur’an was ordered after the Battle of Yamama, where 70 hafiz (people who knew the Qur’an by heart) died. After the event, Caliph Abu Bakr formed a delegation of 12 people in charge of composing the Qur’an into one consolidate text. The delegation, or group of scribes, gathered those who had memorized the Qur’an and materials that contained recorded verses from the prophet’s lifetime. In order for memorizations to be considered legitimate, they had to match – word for word – memorizations recited by at least two other people. Memorized verses were confirmed by recorded material; other times, recorded material was confirmed by legitimized memorizations. Once the verses were confirmed, the group of scribes collected Qur’anic material and compiled a manuscript, or a “mushaf” containing a fixed order. A total of 33,000 companions agreed on the validity of every letter of the Qur’an before its compilation was deemed complete.

Interestingly enough, the mushaf was not compiled chronologically in the order in which the Qur’anic verses were revealed to Muhammad. According to Muslim scholars, verses of the Qur’an were delivered to resolve issues the Muslims were going through at the time. Surahs revealed when the prophet was in Mecca were typically faith-related, pertaining to the oneness of god, patience, and mercy in a time the Muslims were being persecuted and killed. Surahs revealed in Medina (post-migration), were more about structure, justice, and jurisprudence. Muslims believe that Angel Gabriel visited Muhammad before his death and taught the prophet the formal order of the Qur’an – which differed from the pattern in which it was delivered – who then shared the information with his companions before his death. Whether or not this is true, scholars believe that the arrangement of the Qur’an has to do with the grouping of themes and motifs. Muslims do not necessarily read the Qur’an in order from beginning to end like most Western texts; rather the Qur’an is typically read in chunks depending on what message or theme a Muslim is looking to explore or discuss.

After Abu Bakr died, he passed the mushaf, or manuscript to Hafsa, Muhammad’s widow for safekeeping. In 650 CE, as Islam expanded beyond the Arabian peninsula and into Persia and North Africa, Caliph Usmaan ibn Affan noticed discrepancies in the pronunciation of Qur’anic Arabic. To preserve the sanctity of the text, Usmaan ordered that Abu Bakr’s mushaf, manuscript copy be used to create a standard book (al-Qitab). The standard copy was used to create copies of the Qur’an in book form, and all other variant copies were destroyed. Today, each Qur’an is unanimous and identical line for line, word for word, letter for letter. Personal copies, or translated copies are seen as separate from the original text, and each Muslim typically learns Arabic to read the Qur’an in its original textual language to prevent distortion of the content and its message.

Qitab (book) vs. Suhuf (manuscript):

Other Versions

Some Islamic scholars debate the validity of other compositions of the Qur’an. Imam Ali, a companion of the Prophet compiled the Qur’an chronologically in the order in which it was revealed though. Shia scholars claim that Ali was the first to compile the Qur’an – just six months after Muhammad’s passing away. Other Islamic scholars, however, argue that the Qur’an as a text was not meant to be ordered chronologically and that Ali’s version included superfluous interpretations of some verses. The Qur’an as a book was compiled so that any interpretations or information outside of the revealed verses were to be excluded from the holy scripture, and preserved separately outside of the text itself.

Overall, within the Muslim community, there is little dispute on the representation of the canon. The text itself is generally agreed on, though what is debated is the time in which the compilation process took place. While believe it was long after the prophet’s dead, others say it was 20 years after, while others still say compilation began just six months after Muhammad’s death.

Spiritualizing the Manuscript Process

In Aelfric’s Preface to Genesis, the narrator expresses fear of “unlearned priests” taking holy scripture out of context with translation.

Now it seems to me, friend, that the work [of translation] is very dangerous to me or anyone to undertake, because I fear that if someone foolish reads this book, or hears it read, that someone might wish to think that one might live now under the new law just as the old fathers lived, when in the time before the old law was established… For unlearned priests, if they understand only a little of Latin books, then it seems to them that they might quickly be great teachers, although they do not know the spiritual meaning of them, and how the old law was a sign of things to come

The narrator expresses a fear that separating the medium from its message would dilute and contort the message of the Bible. Because Parish priests mainly read in English while Latin was reserved for those higher in the hierarchy of the church, Biblical teachings could only fractionally be taught and learned. Those unfamiliar with Latin reading translations would understand a text removed from its original medium, and therefore from it original message. Further, those who taught the Latin scripture would separate the masses from the scripture as their own personal interpretations of the scripture would dilute the core meaning of Biblical passages.

Similar fears were expressed during the compilation of the Qur’an. The text was preserved in Arabic and was checked for unanimity among different sources (memorizations and recordings). It was also necessitated that the Qur’an be read in the context of the Sirah (the narrative history, behaviors, and sayings of Muhammad) so that the message of the Qur’an would not be taken out of context for material or worldly purposes. The emphasis on preserving the Qur’an in Arabic had to do with a conservative approach in maintaing the language the text was delivered it so to not distort the meaning of the scripture’s intended message. Still, however, to say that the Qur’an lacks limitations in the negotiation of its structure would be incorrect. The destruction of alternative versions of the Qur’an raises questions about the validity of those texts, and if there were other political motives that prompted their destruction. Information surrounding the ordering the Qur’an is vague and still shapes the way the Qur’an is read and understood by Muslims and Non-Muslims alike. Lastly, there is little information on the writing process of Qur’anic compilation. Like mnonks who at times made errors, interpretations, or chages during the transcription process, the same could be possible for scribes compiling the Qur’an and producing more books from the standard copy.

Overall, various measures were taken by early Muslims to prevent de-contextualization of the Qur’an such as preserving Qur’anic Arabic, cross-comparing multiple sources, prevention of translation, and resolving of textual discrepancies (inconsistent words, letters, Arabic dialects, etc). Still, the same issue of separating the medium and message that arose with “unlearned priests” and Biblical passages is repeated in the Muslim world with the Qur’an. The hyper-emphasis of maintaining the proximity of the medium to the message within Qur’anic scripture has made understanding the Qur’an highly esoteric and exclusive. Many Muslims do not speak fluent Arabic, and many who do still have difficulty understanding the Qur’an’s message. Coupled with the fact that the Sirah (the lens through which Muslims interpret the Qur’an) is more accessible to scholars than it is to the masses, understanding the Qur’an is not exactly an easy, or accessible undertaking. Because many lack the tools to read and understand the Qur’an, people still revert to reading translations or listening to interpretations of imams (Muslim priest); as a result, they are further separated from the text and its message. While measures taken to make the Bible more accessible to readers may have distorted its original meaning, measures taken to ensure accuracy of Qur’anic scripture to prevent misinterpretation only created the same distorting effect by further distancing people from the medium and the message itself.

Sources:

“How the Quran Was Compiled After the Prophet

Preface to Genesis Translation

History of the Compilation of the Quran

Oldest Quran Fragments Found at Birmingham University

Image Sources:

FIELDBOOKS